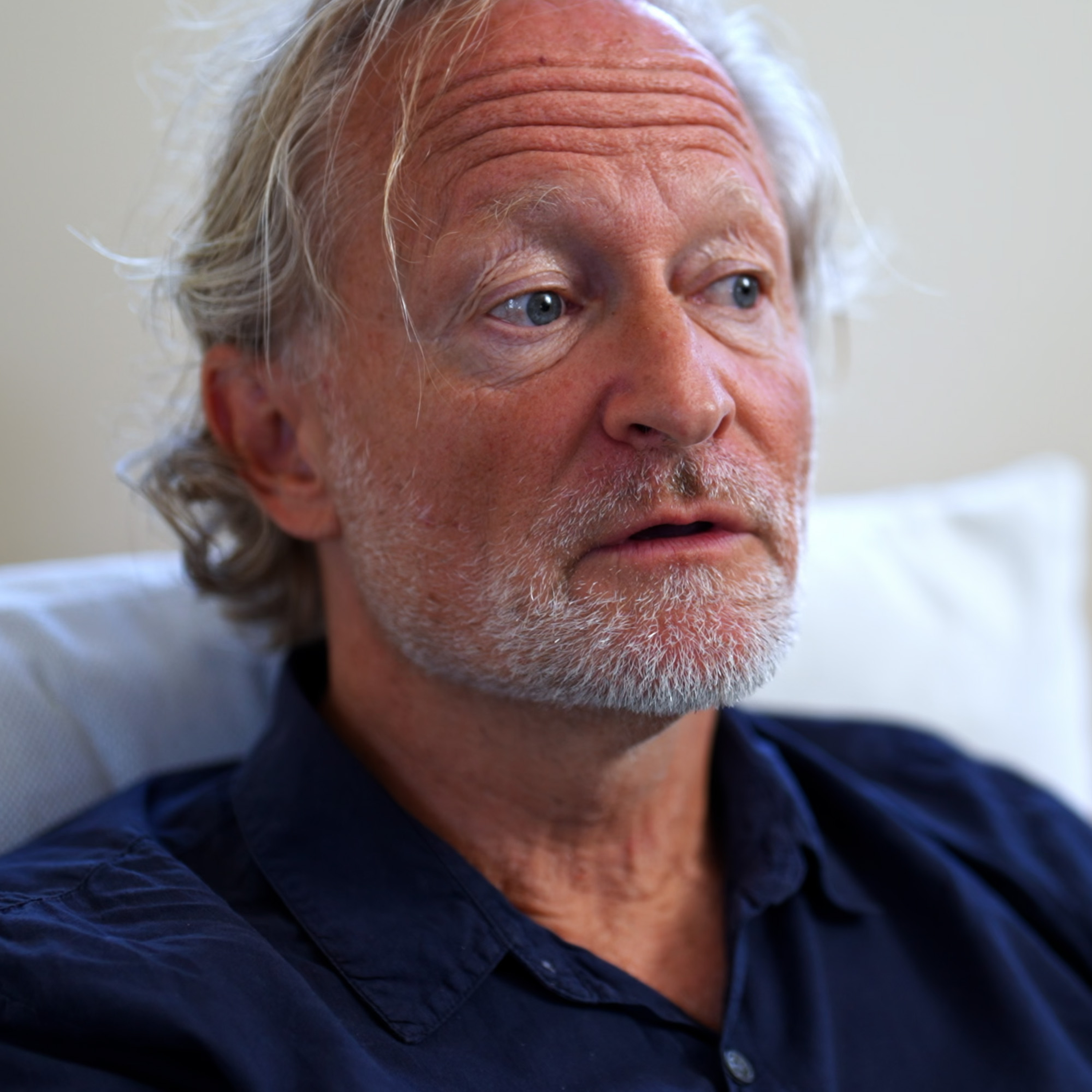

Large Language Models and Emergence: A Complex Systems Perspective (Prof. David C. Krakauer)

Machine Learning Street Talk

What You'll Learn

- ✓Intelligence is about doing more with less, not accumulating more knowledge

- ✓Culture and information storage enable 'light speed' evolution compared to biological evolution

- ✓Emergence in LLMs is characterized by principles like scaling, criticality, compression, and generalization

- ✓The 'cartoonish' view of emergence, such as sudden jumps in capabilities, is critiqued

- ✓Krakauer emphasizes the importance of distinguishing between intelligence and capabilities

AI Summary

This episode explores the complex systems perspective on large language models (LLMs) and the concept of emergence. The guest, Prof. David Krakauer, discusses the distinction between intelligence and capabilities, arguing that intelligence is about doing more with less, while capabilities can be achieved through accumulating knowledge. He also explains how culture and information storage can enable evolution at 'light speed' compared to biological evolution. The conversation delves into the principles of emergence, such as scaling, criticality, compression, and generalization, and how these apply to the development of LLMs.

Key Points

- 1Intelligence is about doing more with less, not accumulating more knowledge

- 2Culture and information storage enable 'light speed' evolution compared to biological evolution

- 3Emergence in LLMs is characterized by principles like scaling, criticality, compression, and generalization

- 4The 'cartoonish' view of emergence, such as sudden jumps in capabilities, is critiqued

- 5Krakauer emphasizes the importance of distinguishing between intelligence and capabilities

Topics Discussed

Frequently Asked Questions

What is "Large Language Models and Emergence: A Complex Systems Perspective (Prof. David C. Krakauer)" about?

This episode explores the complex systems perspective on large language models (LLMs) and the concept of emergence. The guest, Prof. David Krakauer, discusses the distinction between intelligence and capabilities, arguing that intelligence is about doing more with less, while capabilities can be achieved through accumulating knowledge. He also explains how culture and information storage can enable evolution at 'light speed' compared to biological evolution. The conversation delves into the principles of emergence, such as scaling, criticality, compression, and generalization, and how these apply to the development of LLMs.

What topics are discussed in this episode?

This episode covers the following topics: Large Language Models, Emergence, Complex Systems, Intelligence vs. Capabilities, Evolution and Culture.

What is key insight #1 from this episode?

Intelligence is about doing more with less, not accumulating more knowledge

What is key insight #2 from this episode?

Culture and information storage enable 'light speed' evolution compared to biological evolution

What is key insight #3 from this episode?

Emergence in LLMs is characterized by principles like scaling, criticality, compression, and generalization

What is key insight #4 from this episode?

The 'cartoonish' view of emergence, such as sudden jumps in capabilities, is critiqued

Who should listen to this episode?

This episode is recommended for anyone interested in Large Language Models, Emergence, Complex Systems, and those who want to stay updated on the latest developments in AI and technology.

Episode Description

<p>Prof. David Krakauer, President of the Santa Fe Institute argues that we are fundamentally confusing knowledge with intelligence, especially when it comes to AI.</p><p><br></p><p>He defines true intelligence as the ability to do more with less—to solve novel problems with limited information. This is contrasted with current AI models, which he describes as doing less with more; they require astounding amounts of data to perform tasks that don't necessarily demonstrate true understanding or adaptation. He humorously calls this "really shit programming".</p><p><br></p><p>David challenges the popular notion of "emergence" in Large Language Models (LLMs). He explains that the tech community's definition—seeing a sudden jump in a model's ability to perform a task like three-digit math—is superficial. True emergence, from a complex systems perspective, involves a fundamental change in the system's internal organization, allowing for a new, simpler, and more powerful level of description. He gives the example of moving from tracking individual water molecules to using the elegant laws of fluid dynamics. For LLMs to be truly emergent, we'd need to see them develop new, efficient internal representations, not just get better at memorizing patterns as they scale.</p><p><br></p><p>Drawing on his background in evolutionary theory, David explains that systems like brains, and later, culture, evolved to process information that changes too quickly for genetic evolution to keep up. He calls culture "evolution at light speed" because it allows us to store our accumulated knowledge externally (in books, tools, etc.) and build upon it without corrupting the original.</p><p><br></p><p>This leads to his concept of "exbodiment," where we outsource our cognitive load to the world through things like maps, abacuses, or even language itself. </p><p><br></p><p>We create these external tools, internalize the skills they teach us, improve them, and create a feedback loop that enhances our collective intelligence.</p><p><br></p><p>However, he ends with a warning. While technology has historically complemented our deficient abilities, modern AI presents a new danger. Because we have an evolutionary drive to conserve energy, we will inevitably outsource our thinking to AI if we can. He fears this is already leading to a "diminution and dilution" of human thought and creativity. Just as our muscles atrophy without use, he argues our brains will too, and we risk becoming mentally dependent on these systems.</p><p><br></p><p>TOC:</p><p>[00:00:00] Intelligence: Doing more with less</p><p>[00:02:10] Why brains evolved: The limits of evolution</p><p>[00:05:18] Culture as evolution at light speed</p><p>[00:08:11] True meaning of emergence: "More is Different"</p><p>[00:10:41] Why LLM capabilities are not true emergence</p><p>[00:15:10] What real emergence would look like in AI</p><p>[00:19:24] Symmetry breaking: Physics vs. Life</p><p>[00:23:30] Two types of emergence: Knowledge In vs. Out</p><p>[00:26:46] Causality, agency, and coarse-graining</p><p>[00:32:24] "Exbodiment": Outsourcing thought to objects</p><p>[00:35:05] Collective intelligence & the boundary of the mind</p><p>[00:39:45] Mortal vs. Immortal forms of computation</p><p>[00:42:13] The risk of AI: Atrophy of human thought</p><p><br></p><p>David Krakauer</p><p>President and William H. Miller Professor of Complex Systems</p><p>https://www.santafe.edu/people/profile/david-krakauer</p><p><br></p><p>REFS:</p><p>Large Language Models and Emergence: A Complex Systems Perspective</p><p>David C. Krakauer, John W. Krakauer, Melanie Mitchell</p><p>https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.11135</p><p><br></p><p>Filmed at the Diverse Intelligences Summer Institute:</p><p>https://disi.org/</p>

Full Transcript

Close your eyes, exhale, feel your body relax, and let go of whatever you're carrying today. Well, I'm letting go of the worry that I wouldn't get my new contacts in time for this class. I got them delivered free from 1-800-CONTACTS. Oh my gosh, they're so fast. And breathe. Oh, sorry. I almost couldn't breathe when I saw the discount they gave me on my first order. Oh, sorry. Namaste. Visit 1-800-CONTACTS.com today to save on your first order. 1-800-CONTACTS. This episode is brought to you by Diet Coke. You know that moment when you just need to hit pause and refresh? An ice-cold Diet Coke isn't just a break. It's your chance to catch your breath and savor a moment that's all about you. Always refreshing, still the same great taste. Diet Coke. Make time for you time. The brain is an organ, like a muscle. If I outsource all of my thinking to something or someone else, it will atrophy just as your muscles do. There's nothing confusing about that. It's just a fact of physiology. So I'm David Krakauer, and I work on the evolution of intelligence and stupidity on planet Earth. Science is a humanistic endeavour. The purpose of science in the universe is to make the universe intelligible to us. not to control it, not to predict it, and not to exploit it. Science is no different from poetry, is that we're trying to make sense of the world, trying to give it meaning in relation to our own existence. Super intelligence is only interesting to the extent that it makes me more intelligent, not to the extent it makes me more stupid or more servile or more dependent. Who could? that was actually that was sympathy that was sympathy amazing well i think the first paper of yours i i read was a couple of years ago with melanin we interviewed melanie you know about the debate of understanding and language models i think it was called and um at the time there was this fervor you know the this this um hype around And, you know, the sparks of AGI paper, for example, and they had early access to GBT-4 without RLHF. And they were saying, isn't it amazing that we have these emergent capabilities? Yes. No comment. Right. Well, there's just this whole question of, as you know, I mean, what emergence is, what intelligence is, and we can talk about it all. My particular interest is the evolution of intelligence, which I consider extraordinarily varied. So I consider bacteria intelligent, as you probably know. And my basic, I guess one way of framing a lot of this is that, for me, intelligence manifests most clearly when you can do a lot with very little in terms of input. and I'm less and less impressed when you manifest so-called intelligent behavior when you have more and more and more information at your disposal. Yes. And unfortunately, the way that AI has evolved is in the direction of confusing being very knowledgeable with very intelligent, and I think that, in some sense, encapsulates my critique. yes uh you said in your talk yesterday that all of the reasonable definitions of intelligence if anything try to marginalize away the contribution of knowledge it's about you know adapting to novelty adaptivity in general your evolutionary perspective is very interesting you're kind of pointing to this yesterday when you were saying about um the the history preserving and and accumulating information but preserving that history is very important not only phylogenetically but also ontogenically. Can you explain what you mean by that? Yeah, so, I mean, it's a really interesting question, right? I mean, one of the big confusions in the intelligence world is whether we're allowed to call ingenious adaptations intelligent. That is, capabilities, adaptations. Is that an intelligent thing, or is that just what evolution gives you? And there are people out there who would say, no, that's not intelligent, because intelligent isn't a capability, it's the ability to acquire capability. The capacity to acquire capacity, as Woodrow puts it, and Francois Cholet and others like that have adopted that perspective. So the question is, where does that come from? and you can actually derive this mathematically. In the 1970s, a very prominent theoretical chemist who won the Nobel Prize actually for high-speed chemistry, Manfred Eigen, started developing a series of theories that were finally formalized in the 80s called quasi-species theory. And to cut a very long story short, what that theory gives us is a fundamental bound on the rate at which information can be acquired in any evolutionary process. And it turns out that the fundamental speed limit is established by the generation time. So it's essentially one bit per selective death. That even has a name. It's called the Muller Principle. So the way to think about it is you had lots of variants, each of which has a different hypothesis about the world. Selection kills all the ones that have the wrong hypothesis and keeps the one that has the right one. And it turns out that you can only maintain one bit because you don't know which bit would be responsible if it was many. So it's one bit per genome, per generation. Now, if you're a large multicellular organism, all of the adaptive information exists at frequencies that are higher than the generational frequency. So what do you do? So you have to build a system that's extra genomic. Yes. And we call them epigenomes, or we call them brains. and these are systems that can acquire high frequency information that goes beyond the selective dynamic. So that's the basic idea, right? So you can actually make a qualitative distinction and that boundary is called the error threshold where you have to acquire an inferential organ mechanism to extract high frequency information from the world. For some people, that's intelligent. I don't share that view because it's somewhat arbitrary, but it's principled. And you said yesterday that, of course, the nervous system is an example of one of these things, but you said culture is evolution at light speed. What do you mean by that? Well, it turns out, okay, so I don't know how technical we can get. Very technical. Okay, we can get technical. So one way to think about this, right, is that imagine a genome as being a point in a configuration space. It's called sequence space. And as you evolve, you move around in this space. You can think of it as a graph where adjacent nodes are connected through mutation, which tends to be local, not always. Okay. So the eigen theory tells us how much information it can be preserved at a certain rate of mutation, or what's the fastest speed you can move adaptively in sequence space and not lose everything you've acquired about the past. And this is the error threshold. if you're in a position to take the information that you've acquired in the past and store it refrigerate it quite literally put it in a library put it in a book now you can move on that graph much more quickly because you're not corrupting the information that you have hitherto accumulated and so culture actually has no upper bound because as long as i store like save to my hard drive save to my library the information that I've acquired up to now, I can just randomly produce variants at any rate. As long as one of those is good, I add it to my library. So culture actually breaks evolutionary light speed and is a qualitatively different process of evolution to organic evolution because of that. And David, you're at pains to distinguish capabilities from intelligence. So why is culture or a library a form of storing, I don't know whether you would call it intelligence? Well, okay, again, I don't think so. I wouldn't. I make a big distinction between knowledge and intelligence. And we talked about this, which is that smart people don't need a lot of knowledge to solve a problem. Not so smart people do and that's our experience in life you know as you go to a friend who's swatted up on all of the solutions to the problems and you ask them and they answer you're not as impressed as that friend of yours you spent the last week you know at a pub or on a hike not in the library those are the people who impress us more and I think we've lost track of that actually I think that as I like to put it um when it comes to intelligence less is more and not more is more yes indeed yesterday you you said that yes so intelligence is is doing more with less and you actually said stupidity is is doing less with more which was which was very interesting well no again i mean so okay so the whole um so let me give you the background to that so at sfi we're very interested in this idea of emergence and Phil Anderson in 1972 wrote a very famous paper called more is different and Phil was reacting to high energy physics high energy physics deals with very small things where the symmetric laws of physics produce a corresponding symmetry in the configuration of states in the physical system but as you make things larger and he gives the example of nh3 and ph3 ammonia and phosphine the underlying laws of physics and protein folding are symmetric but when you have a very large structure it gets stuck in a potential well and so you break the symmetry so it doesn't matter if the law is symmetric it's like saying i have a ball rolls down a hill rolls into a very deep valley it gets stuck and uh there's an energy funnel and it doesn't matter that the law is symmetric because now the only thing that's going to tell you what state you observe is the initial condition where you started in the landscape and his point this is called a broken symmetry and phil's point was as you get larger and larger but hence more in this particular instance in terms of the atomic mass of the molecule, you're more and more likely to have to use an additional parameter to tell you where you are. And the consequence of that is that if you're going to have a theory now, which isn't just a description, a list of initial conditions, in other words, you have to take averages you have to do core screening yes and that's the foundational principle of complex systems that in order to go from a very non-parsimonious microscopic description to a parsimonious macroscopic one you have to take averages in a clever way and that's the essence by the way of emergence yes indeed and we should talk about your paper so recently released Large Language Models and Emergence, a Complex Systems Perspective. And as you were just alluding to, emergence is more is different. And in a minute, we'll talk about scaling, criticality, compression, novel bases and generalization as being the principles of the measures. But just rewinding a tiny bit, many folks in the LLM literature famously Jason Way I was speaking with Daniel Hendricks last night and he actually told me that he said it first even before Jason And they have this rather cartoonish version of emergence, which is something along the lines of when there is a sharp discontinuity in capabilities, we can say that, and they gave examples, didn't they, of three-digit multiplication. And because you have these scaling laws, and then you see these divergent appearances of capabilities you're having none of that day well the joke there there's a few things to say exactly you just put it very well and so and you don't need to repeat it but yeah so this three-digit addition that goes from being i can't remember the percentages right but let's say that they're under 50 when you've got 100 billion parameters and they go to 80 you've got 175 billion or something like that. And you think, well, okay, I can do three-digit addition very effectively on an HP35 calculator with a 1K ROM. But that's an order of a billion times smaller memory footprint. So you think, okay, so you can engineer a solution into a tiny little memory footprint very efficiently using approximations that we are familiar with. Or you have to train it with all the data in the world at considerable expense it does lots of other things in addition to right that's the interesting point to three-digit addition and you call it emergent i would simply call that really shit programming right in other words i think that is the right way to talk about it and if you're doing really shit programming with natural language you need loads of it to achieve the goal of interest the fact that it's discontinuous is neither here nor there. I think that's almost an irrelevance. And it's never really had much to do with the emergence debate, except as an analogy to what are called first order phase transitions, which are sort of where essentially the first derivative of the free energy of the system in relation to some, let's say, control parameter, let's say temperature, is infinite. And so there are these technical definitions in relation to theory of phase transitions but this is nothing like that and we can talk about that because a phase transition is characterized by a demonstrable change in the internal organization of the system that's really what it's about it's not about the discontinuity that's that's superficial yes yes so so broadly speaking you think it's about this coarse graining where there is an entirely novel description using novel bases to you gave the example in the paper actually of you know a microscopic description could be of how molecules interact with each other a macroscopic version would be something like navier stokes so fluid fluid dynamics and this is an entirely kind of um aggregate description of the system which only works at a certain scale right and notice that's completely non-discontinuous you know how when does something cease being the atomic theory of gases or h2o molecules and when are you really at the hydrodynamic limit where you can write down newton's laws of compressible incompressible fluids navy stokes equations and well it there isn't there isn't this magic discontinuity it's just a it's a limiting process and and yet to this idea of intelligence which is you know about doing more with less um now all of a sudden you don't have to track all those molecules anymore you can just look at the average densities and um so the key point here of emergence for many of us is there's a sufficient change in the internal organization of the system that you can get this more parsimonious description of its behavior and which screams off that sort of term of art um the contributions of the molecular degrees of freedom. You don't need to track them. They won't help you. They're surplus to the prediction that you're trying to make. Yes, indeed. So for you, David, when we saw, when we would see a break with scaling laws, so right now we are memorising everything, capabilities and scaling laws are commensurate. There have been studies, Dan Hendricks last night said it's something like 96% correlated. you would expect to see a deviation. So when we can have intelligence without scaling, that would actually imply that some kind of coarse graining has been established. Yeah, that's interesting. I think, yeah, because sometimes it's called the breaking of scaling. So scaling laws are not evidence of emergence. Yes. So the most famous example that we work on at SFI, my colleagues Jeff West and Chris Kempis and others, is alimetric scaling. It's good that we're in St. Andrew's, right? Because Darcy Thompson, the great Scottish mathematical biologist, essentially invented the field in his beautiful book on growth informally, published in 1917. I went to see his collection this morning here. So that's an aside. But this theory tells you that at all scales, you'll have a fixed relationship between mass and metabolic rate. Okay. And it comes out of an optimization principle that applies at all scales, which is very interesting. There's nothing emergent about it. Emergent means there's a change in the organization which requires a new scaling law. And again, there's quite a lot to say about this, but minimally, right, to start investigating a potential case of emergence, you would want to see that the scaling law is broken then secondarily you'd have to go inside the system and ask why and this is the big i think objection that melanie john and i have to emergence claims is they're based only on the external manifestation of a task and not on the corresponding internal microscopic dynamics which you want to somehow map onto the macroscopic observable. That's the essence of emergence, the micro to macro map. This is just macro. Yes, indeed. And I'm a massive fan of Melanie, probably her biggest fan, actually. And she did this copycat work for her PhD thesis. And because I suppose the question is, what does course grading look like for language models? What would it look like? Analogy is a wonderful candidate. And more broadly, I think what you're pointing to is that these models learn fractured, entangled representations. They're microscopic representations. And what we would expect to happen if they were emergent would be that they would learn these factored, unified representations which correlate with the world, which carve the world up by the joints. And perhaps you would extend that and say, actually respect the phylogeny, things like symmetry. You know, they respect the way that the world works, which means that they would be able to take creative, intuitive steps because they know how they got there. Yeah. And that's a very good point. I think that's exactly right. I think that, I mean, it's a deep question, right? But I think there's a sense in which our nervous system and our bodies respect certain fundamental constraints in the physical world, is what you're alluding to. And, you know, and this has been borrowed, of course, by neural networks in things like convolutional neural nets. Because then you're saying there is a structure in the world which there tends to be some covariance in visual scenes and convolutional networks capture that covariance very naturally. So that's an example of using a stronger prior which respects something you know about reality. there is a little bit as you know very well in the neural net community a bit of an allergy against building priors into models because you want to do it all kind of inductively which is a little bit of a confusion it seems to me given that the entire structure derives from 1943 mccullough and pitts which was a nervous system inspired concept so why not use a bit of world inspiration too. Yes, indeed. You mentioned yesterday the road to reality by Penrose. And funnily enough, I interviewed Michael Bronstein, who is one of the founders of this geometric deep learning idea. And it is basically Platonism, right? So it's, you know, let's imbue all of these symmetries, because we think that the generating function of the world is constrained by these symmetries. And it's an abstraction, which doesn't leave out any detail. Are you amenable to that i mean i'm not because it's so anti-complexity i mean i might be tears i'm to be honest i'm not familiar with it um sometimes the way i like to put this is you know in 1918 the great mathematician physicist emmy noto yes um conservation laws yeah right one of those sort of hidden figures by virtue of sexism in society um publishes a very very important piece of work where she shows a relationship between the symmetries of the action functional yes the symmetries of the of the lagrangian um the principle of least action that captures the principle of least action and showed right that um shifting the time or space coordinate corresponded to the conservation of a particular physical observable. Change time and you conserve energy. Change space and you conserve momentum. And Darwin is in some sense anti-notar. The origin of species says change time, everything's different. Change space, everything's different. And this gets to the Anderson broken symmetry idea. that it's unlike physics because it's not symmetry dominated and consequently various observables are not conserved so i actually think the power of symmetry simply ceased to be the important organizing principle once life came into existence and certainly intelligence so i'm not sure what he's claiming um that's different by the way to saying that there are symmetries in the world that perception exploits that's clearly true and i don't again i don't know if that's the how convergence do you think evolution is if we ran it in a parallel universe a thousand times you know did you think there's this kind of real ontological coupling or is it quite divergent oh that's a good question depends who you ask right what would you say very um if you ask gould very not, or not very. I think it sort of depends on the resolution of your measuring device. Because at a very coarse-grained level, allometric scaling theory says everything scales in the same way. It doesn't matter how many times you run it. The scaling of essentially energy to mass is dependent entirely on the dimensions of space. The three-quarter scaling law is three dimensions of space over four dimensions of space, where the extra dimension is fractal. That has nothing to do with life. I mean, it has something to do with life, of course, but it doesn't depend on a contingent history of life. So at that level of granularity, if that's all you could see, all you could measure, the average mass of an organism, there would be no variation, right? I mean, very little. But if you zoom in, then of course you see more and more variation, which is a, if you like, a kind of fossil record of its unique history. And biologists do tend to zoom in. Psychologists do tend to zoom in. I think that's almost dispositional. Physicists like the granular, the very non-granular, averaged. but I don't just like the very natural historical. It's not surprising that those two traditions come to different answers. Yes, indeed. Could you explain what you mean by this distinction of knowledge out versus knowledge in with emergence? Yes. Okay. So first of all, let's just establish that with emergence we mean that there is a description of a system that's more parsimonious that a given level of observation does not benefit from more microscopic detail. We gave the example of fluids, right? There are many. So how does it come about? How does emergence come about? And there's an infinite number of examples. But physicists tend to be interested in how many identical particles all subject to the same context or environmental inputs, experience emergence. I gave that example, add molecules, change the temperature. That's just one dimension, the average energy. When it comes to evolution or learning, there isn't one input that every molecule is experiencing. You're not just changing the temperature uniformly. Everyone is experiencing a different, unique parameterization. So the theory of emergence was developed mainly in the physical domain, where you had large numbers of identical things with a global signal. And now emergence claims are being made for large systems of non-identical, all experiencing a unique signal. So there's already this question of whether or not we can even talk about emergence. And we don't typically, by the way, because we talk about evolution, we talk about learning, development, and engineering. No one would say an iPhone is emergent, because you say it's somewhere, there's a plan that tells you exactly what to do with every component, just as there's a plan that tells you what to do with every cell in development. That's a complex distributed plan, part genome, part environment. But nevertheless, there's an abstraction in which you could talk about it in that way. So knowledge in are systems where essentially you have to, to get the structure of interest, the pattern of interest, you have to parameterize each component individually, more or less. knowledge out is the example of physics where you say all I did was change the temperature and I got a solid from a fluid I got a plasma, what happened? this is a completely different state of matter and all I did is change one thing and so that's the big distinction, so the challenge I think for biology and machine learning is how to talk about emergence when you've sort of violated the prime directive which is you've been allowed to have local modification of each component um and i think you can but that's the essential distinction between knowledge and knowledge one thing that fascinates me about emergence is um we'll get on to agency i think of that as a as a form of causal shielding or causal disconnectedness certainly from the perspective of an observer but there are philosophers like um george ellis i believe who said that um causation is kind of shielded between the levels and causation happens between the levels but i mean to you what is the relationship between causality and emergence oh that's interesting i mean i think in a way one way to say it right everything i've said sort of trivially is that you do have a new coarse-grained set of effective mechanisms that you can talk about as being genuinely causal in the interventional sense of power not in the fundamental newtonian sense and and these are complementary conceptions of causality right um but i think i would say it would be completely reasonable to restate the emergence claim as a more parsimonious causal mechanism yes right that there is an aggregate observable that conforms to your preferred neoparl framework that sort of works with the do operator and the appropriate treatment of conditional distributions and um so i think that is appropriate to think of it as a new form of causality. Fascinating and on this notion of of agency how would you define it in relation to things like intelligence I mean just me just very personally there's there's the the autonomy and the causality thing but there's also this intentionality and directedness thing so it's it's not about just autonomy in one direction it's the ability to set your own direction and yeah just what does that mean to you? Yeah so I've actually been developing a framework for thinking about this and the way i think about it is in in three different more sophisticated conceptions the first is the conception of action from physics yeah balls roll downhill yes you wouldn't call that agentic some people probably do unfortunately but okay that's the simplest we have a perfectly good newtonian nagrangian hamiltonian theory we don't need to use these words agentic for that some people okay then we have this darwinian concept adaptation but adaptation is a bit more than a ball rolling down a hill because it says that the ball gets better at rolling down the hill because it has an internal record of its past efforts and the general term that kant gave to that and john holland gave to that and marie gilman gave to that is a schema okay um it's a it's a you can think of it as a simple lookup table it says if i find myself in this situation i should do that if i find myself in that situation i should do that a bit different from the moon a bit different from a ball and then the most sophisticated to me would be the agentic and that adds something to the adaptive which is a policy it says this is what i want to do notice adaptation could just be reactive you could say if i find myself here then do that. Policy actually says, I would like to do this into the future. So I think there's a very nice spectrum that takes us from fundamental conception of theoretical physics through to a conception in evolutionary theory through to a conception that seems to be appropriate for a psychological or cognitive system. And they're adding, if you like, complication to the internal schema to accomplish that particular objective. And does agency entail this kind of emerging coarse graining that we were speaking about before? It certainly seems to. We look in the natural world and we see planets, we see things, but then there are these agents that have a level of sophistication which is much greater than that. And would that be an example of this kind of coarse graining you're talking about? I think for us to understand them, the answer is definitely yes. there's a secondary question of what we sometimes call endogenous core screening. And that's where it gets more complicated philosophically. Because when we reason, let's say I think I'm reasoning with language, but I'm still recruiting millions of neurons to do it. And so at the level, if I was a solitary agent, it would be very difficult to know whether I'm really doing endogenous core screening. The data for endogenous core screening comes from communication. So if I tell you, you know, Tim, this is what it means to integrate by parts or something. This is what a Fourier transform does. And you look at it and say, oh, thank you, I know how to do it now. Now I've actually communicated to you a very low dimensional symbolic scheme which you can then kind of use to program, if you like, your neurons. And at that level, I think, no doubt, because there we've actually done coarse-graining quite demonstrably, and it's actionable on what your neurons are doing. So I think this is Wittgenstein's private language problem. If all you get to do is observe a system in isolation, I would never know. But I think in this social collective intelligence setting, I think it goes without any shadow of doubt that there's evidence of emergence. Can we go over to expodiment? And by the way, I'm a big externalist myself, but I hadn't come across the term expodiment, which has a very specific meaning. Yeah. So I was very interested in this idea of embodiment, which we're all familiar with, which is that we can outsource computation to constraint. We can use the reduced degrees of freedom of a limb to reduce the complications of our policy. Okay, everyone knows that. But what about an object in the external world? What about a pencil? What about a fork? What about an astrolabe? What about a Rubik's Cube? And there, it's not embodiment. It's something else, and the something else there requires contributions from culture, right? In other words, no one person built the chessboard, lots of people did together, and they collectively discovered a very effective representation of a certain kind. That's one part of it. So let's make a distinction between the ex-bodied, which is collectively arrived at, versus embodiment, which is your characteristic. the second point about exponent is that interests me is how we have to go via an external material vehicle to get back into the brain and the example i like and there are many examples let's give some simple ones a map so we collectively make a map of this city of st andrews but you can give that to me and i can memorize it and i can burn that map and as we discovered this morning i'm not very good at navigating. So, and I'll be able to navigate freely without a physical object. And this feedback between the collective construction of an ex-bodied artifact and its internalization into the individual mind, I call the expodiment helix. And it just gets better and better and better, right? Because now I have a map, I can explore more of the space, I can contribute to that collective script, which you can then internalize into your mind. This is a very under-theorized process, and we've been working on it very carefully in the last several years in relation to problem-solving artifacts, like the abacus, like the soma cube, like the Rubik's cube. How does that dynamic work? What does the physical object do that your brain cannot? And we can talk about that, but we can quantify that quite exactly. Does it ever feel like you're a marketing professional just speaking into the void. But with LinkedIn ads, you can know you're reaching the right decision makers, a network of 130 million of them. In fact, you can even target buyers by job title, industry, company, seniority, skills. And did I say job title? See how you can avoid the void and reach the right buyers with LinkedIn ads. Spend $250 on your first campaign and get a free $250 credit for the next one. Get started at linkedin.com slash campaign. Terms and conditions apply. This is Jason Momoa. I'll be your finance professor today. Welcome to Banking Smarter 101 with Chime. Bam! First lesson, sign up for Chime and set up direct deposit. You'll be joining millions of members banking fee-free. Second lesson, get cash back on eligible purchases while building credit. And a higher APY on your savings. That's how you bank smarter this season. Fa-la-la-la-la, class dismissed. Join Chime today. Chime is a financial technology company, not a bank. Banking services and a secure Chime Visa credit card provided by the Bancor Bank NA or Stride Bank NA. Members FDIC. Optional services and products may have fees or charges. Details at Chime.com slash fees info. With a qualifying direct deposit, earn 1.5% cash back on eligible secure Chime Visa credit card purchases. On-time payment history may have a positive impact on your credit score. Results may vary. APY means annual percentage yield. Learn about credit building and more at Chime.com. David, your institute has done some fascinating research on collective intelligence in general. I know it sounds like a contrived question to ask, but what is the relationship between, or maybe what is the boundary of the individual mind to the collective? I think that's a really hard question to answer. So I've worked on these mathematical formalisms for finding boundaries. Many people are interested in them. I call it the informational theory of the individual. There are theories of Markov blankets that you're familiar with. So there are many of you interested in this question of where do you draw it, the boundary? And I think the reality is you can draw many. And so let me just give an example from biology and then come back. So what's an individual ant, you know? Well, all the workers are clones. So you say, maybe that's not really the individual, that's a constituent of the individual. That's like a cell in you. But there is a level of observable resolution where you could say a cell is individual It is dividing semi So a lot of it has to do i think again back to that really critical conception of scale of observation um the formalism that we started developing was one that was scale dependent it says at a given scale of observation the key characteristic of the bounded object is that it contains sufficient information to propagate itself into the future. You don't have to look elsewhere. And clearly that's true for a cell over a given number of divisions at the resolution of the cell. So it's individual. It's not entirely true for the body because, of course, that doesn't really propagate into the future. It's true for your genome, which does partially propagate into the future. it's true for ideas which are partially carried by many minds. So if you ask me to propagate the work of Einstein into the future, you'd get a fairly incomplete jigsaw puzzle. But if you took a group of people, it would probably be quite complete. So it really depends, again, on the complication, the size of the object, the artifact, the concept. how many informational contributions you require. And the theory tries to calculate that over a particular time scale and a particular space scale. So mind is so fascinating because it would depend what you said. If it was my preference for a certain flavor of ice cream, you don't need many, you don't need much collective intelligence for that. But when it comes to things that we actually care about, like, you know, affine projective geometry, unless you have a coxeter who can do it on his own, you need a bunch of us to do it together. So even that's interesting, right? Because there's heterogeneity in this individuality with respect to what can reliably propagate information into the future. It's very difficult. Yes. Yes. You reminded me of my friend, Ken Stanley. I'm sure you're familiar with this. He visited us. He was on sabbatical as a fight. He's my hero. We've just had him on the show. And he was talking about the need for evolvability. So certainly when we have representations, it's not about, you know, where you are, it's how you got there, but also where you can go from there. And agency has a little bit of a shared principle in the sense of, you know, it's about controlling or modifying the environment to meet your goals and so on. And here you're talking about this general principle of information propagation into the future. Yeah, no doubt. And that's a really interesting point because you're not only propagating the variation, the information in the Shannon sense, but the variational operator. Yes. Right. Which could be mutation. It could be different mechanisms of imagination or novelty generation. Yes. And so that's actually a very good point that even within genetics, right, you don't only propagate the genes, but the mechanism of genetic segregation. So, David, you've looked at various forms of sort of representation and computation, organic, inorganic, cultural, etc. Can you tell me about that? Yeah, one way to think about this, and it gets to our opening conversation about the limits of evolution and why brains and minds had to evolve to capture information that couldn't be captured by natural selection. another way to say that right is that we've transitioned from a more mortal style of doing information processing bacteria and so on which are very dependent on life and death for the information to be captured and stored versus us where in some sense much of the information is stored in culture itself so it has more of an immortal flavor and if you think of us as analogous to cells in a body that turn over quickly we turn over relatively quickly relative to the edifices of knowledge that we construct so i actually think you could argue that evolution itself as a program as a process has moved from more mortal styles of computing and i mean information processing in the organic setting, to more immortal-like things which we're familiar with with software and hardware. And you might argue that technologies, and I have argued this actually, why do they exist? And the way to think about this is, we have technologies for everything that we're bad at. We don't play tennis well with our hand. People do, but it's not quite as exciting as watching Roger Federer or what have you. We don't calculate well, hence calculators in the abacus. We walk well, right? And we sing well. So these are things that we don't really have technologies for. They're also harder to build. And there's a sense in which computers and software and archives more generally, bodies of knowledge, represent an inevitable contribution that complements all those domains in which human reasoning is deficient. I mean, that's one way of thinking about it. My biggest fear is not that, you know, AI and chat GPT and all of this will degrade our thinking and creativity. It's that it already has. Well, that's another point, right? Okay, so that's, again, an interest of mine. So I just wanted to make that point that these technologies exist for a reason, and they're there to, in some sense, complement deficits. I'm not saying they're more intelligent than us at all. That's quite the opposite. I think they're intelligent the way a calculator is. So they're compensating for things that we don't do well. There's this other question which is really important, and you can actually generalize. the eigen theory, and this is a little bit maybe technical again, which is that you can show that in the same way that we outsource to the body and we outsource to artifacts as a means of increasing fidelity and reducing energy requirements, we will outsource everything, right, if we can and uh and we see evidence of this all the time and the the most obvious example is the difference between outsourcing to maps versus outsourcing to gps where if you have guaranteed a system that's more effective at navigating the new there is no reason for you to acquire that skill and i think we're already seeing evidence and there's lots of studies actually some recently came out, suggesting that human cognition is attenuating by virtue of outsourcing it to calculators. And I actually, it's one of the reasons why I'm not very optimistic about technology, because up until now, you could argue it was net positive, right? No one's going to argue with a sextant, right, or with a slide rule or something. You think, yeah, that's great. You know, I couldn't do it otherwise. But I think you now can argue with the idea, or be a proponent of the idea, that the long-term implication of technology is the significant diminution and dilution of what it means to be a human. I now receive, on a daily basis, tens of emails written as collaborations between humans and LLMs, and it's 100% rubbish. And I think that the ratio of the human to the LLM is just going to keep going down, and eventually everyone will sound the same. So it's not to suggest that the tool can't be useful, but this evolutionary drive to increase fidelity and reduce energy is so strong in us that we will eventually outsource ourselves. And I think I don't know why people are excited about the technology if that's the likely omega point of the evolution of the species. Yes. Could we expand more on this diminution of, you know, agency and creativity and thinking? I mean, in universities, will we need to almost create separated areas for the students to actually think and read books and do work without AI. Another thing is, you know, we don't believe in this super intelligence idea, but if super intelligence were invented, because the folks in Silicon Valley, they are saying that don't worry about labor anymore, the old way of, you know, doing useful economic tasks. Now we just need to buy lots of GPUs and we need to, you know, sort of defend the GPUs because people might want to bomb the GPUs because they're the source of all power. And that's very much their view. Would that change if we did have super intelligence? There is a world where I would delegate the gym to you. I'm not going. There's no point me going, because you can go for me. I'm not going to get up and walk around, because you can get up and walk around for me. The consequence of that would be, as you know, significant trauma. to our physiological and mental well-being. Everyone understands that. The brain is an organ, like a muscle. If I outsource all of my thinking to something or someone else, it will atrophy just as your muscles do. There's nothing confusing about that. It's just a fact of physiology. And now you might say, just as long as i have people who can carry me everywhere whenever i need to be carried then it doesn't matter that i lose my legs you know and um okay so there is a sense in which we become you know the male deep sea angler fish that's just a testicle uh that's reduced to its absolute minimum for retaining individuality in the sense of propagating information forward in time. It's not a future that I consider desirable. So superintelligence is only interesting to the extent that it makes me more intelligent, not to the extent it makes me more stupid, or more servile, or more dependent. And it just seems to me so glaringly obvious a remark that I don't understand why people are falling for the moonshine. David, it's been such an honor having you on the show. Thank you so much for joining us. Thank you. It's been fun. So I'm David Krakauer. I'm a faculty member at the Santa Fe Institute. I'm also the president of the Santa Fe Institute. And I work on the evolution of intelligence and stupidity on planet Earth. Incredible. David, this has been great. Thank you so much. All right. One of my favorite interviews. None of your community. What the fuck's he talking about? No, no, no. Liberty. Savings very underwritten by Liberty Mutual Insurance Company and affiliates. Excludes Massachusetts. With stays under $250 a night, Vrbo makes it easy to celebrate sweater weather. You could book a cabin stay with leaf views for days. Or a brownstone in a city where festivals are just a walk away. Or a lakeside home with a fire pit for cozy nights with friends. Or, if you're not a sweater person, we can call it corduroy weather. We're flexible. And with stays under $250 a night, you can book a home that suits your exact needs. Book now at Vrbo.com.

Related Episodes

The Mathematical Foundations of Intelligence [Professor Yi Ma]

Machine Learning Street Talk

1h 39m

GPT-5.2 Can't Identify a Serial Killer & Was The Year of Agents A Lie? EP99.28-5.2

This Day in AI

1h 3m

#227 - Jeremie is back! DeepSeek 3.2, TPUs, Nested Learning

Last Week in AI

1h 34m

Pedro Domingos: Tensor Logic Unifies AI Paradigms

Machine Learning Street Talk

1h 27m

Claude 4.5 Opus Shocks, The State of AI in 2025, Fara-7B & MCP-UI | EP99.26

This Day in AI

1h 45m

Is Gemini 3 Really the Best Model? & Fun with Nano Banana Pro - EP99.25-GEMINI

This Day in AI

1h 44m

No comments yet

Be the first to comment