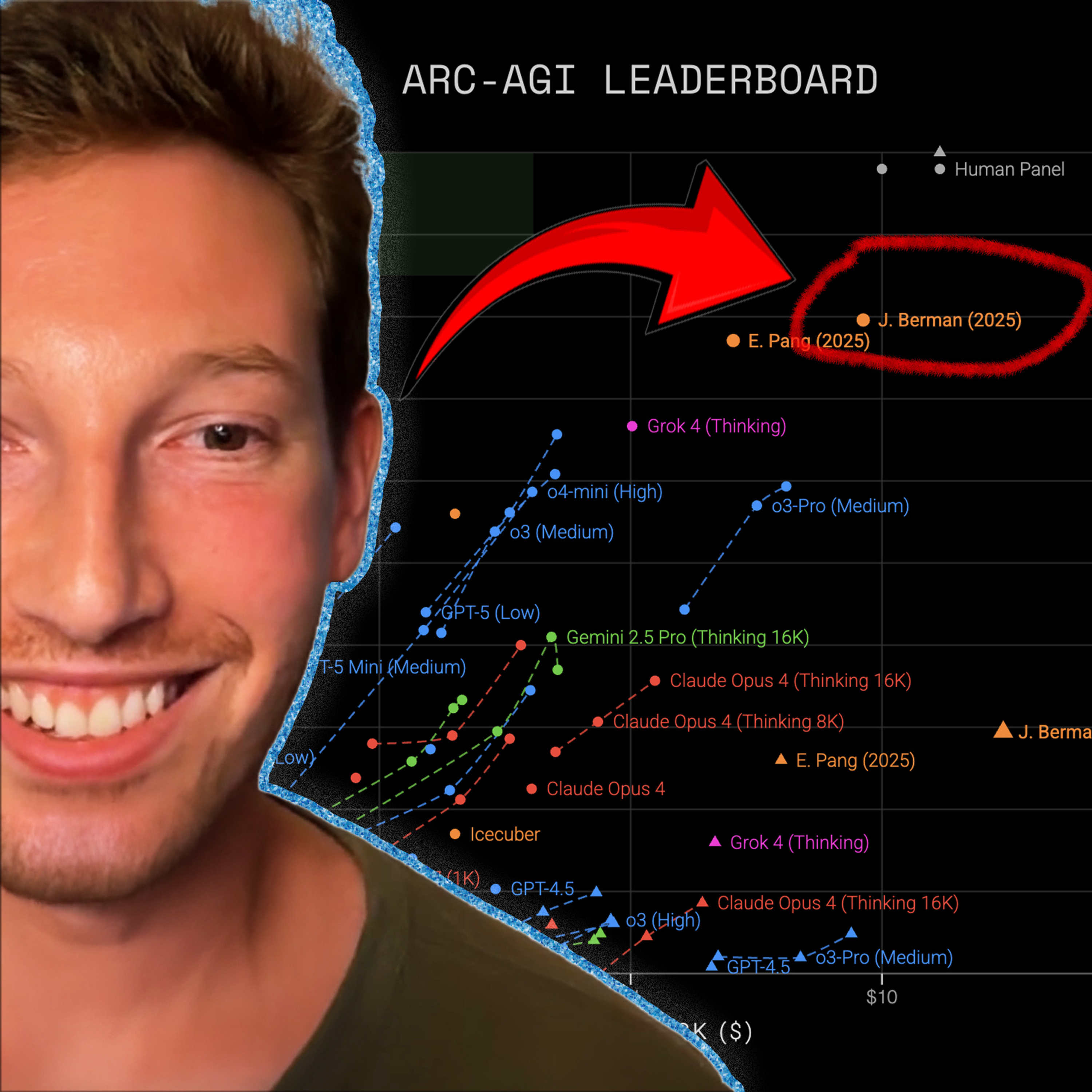

New top score on ARC-AGI-2-pub (29.4%) - Jeremy Berman

Machine Learning Street Talk

What You'll Learn

- ✓Jeremy Berman is a research scientist at Reflection AI who recently achieved the top score on the ARC-AGI-2-pub leaderboard using an evolutionary approach.

- ✓Berman's approach generates descriptions of algorithms and iteratively refines them, rather than generating explicit code.

- ✓Berman believes that language modeling with reinforcement learning is crucial for developing AI systems that can synthesize new knowledge and understanding.

- ✓The ARC challenge is designed to test a machine's ability to extrapolate transformation rules from a few training examples, which is easy for humans but difficult for current AI systems.

- ✓Berman's initial approach was inspired by Ryan Greenblatt's work on generating and refining Python programs, but he found that language models struggled with small errors even on easy tasks.

- ✓The second version of the ARC challenge features more compositional tasks that require multiple iterations, which Berman's evolutionary approach was able to handle better than his previous solution.

AI Summary

The episode discusses Jeremy Berman's recent success in the ARC-AGI-2-pub challenge, where he used an evolutionary approach to generate and refine descriptions of algorithms rather than explicit code. Berman explains his background in AI research and his belief that language modeling with reinforcement learning is key to achieving generalization beyond current AI systems. The discussion also touches on the importance of compositional and symbolic reasoning in AI, as well as the use of human data to evaluate and fine-tune AI models.

Key Points

- 1Jeremy Berman is a research scientist at Reflection AI who recently achieved the top score on the ARC-AGI-2-pub leaderboard using an evolutionary approach.

- 2Berman's approach generates descriptions of algorithms and iteratively refines them, rather than generating explicit code.

- 3Berman believes that language modeling with reinforcement learning is crucial for developing AI systems that can synthesize new knowledge and understanding.

- 4The ARC challenge is designed to test a machine's ability to extrapolate transformation rules from a few training examples, which is easy for humans but difficult for current AI systems.

- 5Berman's initial approach was inspired by Ryan Greenblatt's work on generating and refining Python programs, but he found that language models struggled with small errors even on easy tasks.

- 6The second version of the ARC challenge features more compositional tasks that require multiple iterations, which Berman's evolutionary approach was able to handle better than his previous solution.

Topics Discussed

Frequently Asked Questions

What is "New top score on ARC-AGI-2-pub (29.4%) - Jeremy Berman" about?

The episode discusses Jeremy Berman's recent success in the ARC-AGI-2-pub challenge, where he used an evolutionary approach to generate and refine descriptions of algorithms rather than explicit code. Berman explains his background in AI research and his belief that language modeling with reinforcement learning is key to achieving generalization beyond current AI systems. The discussion also touches on the importance of compositional and symbolic reasoning in AI, as well as the use of human data to evaluate and fine-tune AI models.

What topics are discussed in this episode?

This episode covers the following topics: Evolutionary algorithms, Program synthesis, Language modeling, Reinforcement learning, Compositional reasoning, Symbolic AI.

What is key insight #1 from this episode?

Jeremy Berman is a research scientist at Reflection AI who recently achieved the top score on the ARC-AGI-2-pub leaderboard using an evolutionary approach.

What is key insight #2 from this episode?

Berman's approach generates descriptions of algorithms and iteratively refines them, rather than generating explicit code.

What is key insight #3 from this episode?

Berman believes that language modeling with reinforcement learning is crucial for developing AI systems that can synthesize new knowledge and understanding.

What is key insight #4 from this episode?

The ARC challenge is designed to test a machine's ability to extrapolate transformation rules from a few training examples, which is easy for humans but difficult for current AI systems.

Who should listen to this episode?

This episode is recommended for anyone interested in Evolutionary algorithms, Program synthesis, Language modeling, and those who want to stay updated on the latest developments in AI and technology.

Episode Description

<p>We need AI systems to synthesise new knowledge, not just compress the data they see. Jeremy Berman, is a research scientist at Reflection AI and recent winner of the ARC-AGI v2 public leaderboard.**SPONSOR MESSAGES**—Take the Prolific human data survey - https://www.prolific.com/humandatasurvey?utm_source=mlst and be the first to see the results and benchmark their practices against the wider community!—cyber•Fund https://cyber.fund/?utm_source=mlst is a founder-led investment firm accelerating the cybernetic economyOct SF conference - https://dagihouse.com/?utm_source=mlst - Joscha Bach keynoting(!) + OAI, Anthropic, NVDA,++Hiring a SF VC Principal: https://talent.cyber.fund/companies/cyber-fund-2/jobs/57674170-ai-investment-principal#content?utm_source=mlstSubmit investment deck: https://cyber.fund/contact?utm_source=mlst— Imagine trying to teach an AI to think like a human i.e. solving puzzles that are easy for us but stump even the smartest models. Jeremy's evolutionary approach—evolving natural language descriptions instead of python code like his last version—landed him at the top with about 30% accuracy on the ARCv2.We discuss why current AIs are like "stochastic parrots" that memorize but struggle to truly reason or innovate as well as big ideas like building "knowledge trees" for real understanding, the limits of neural networks versus symbolic systems, and whether we can train models to synthesize new ideas without forgetting everything else. Jeremy Berman:https://x.com/jerber888TRANSCRIPT:https://app.rescript.info/public/share/qvCioZeZJ4Q_NlR66m-hNUZnh-qWlUJcS15Wc2OGwD0TOC:Introduction and Overview [00:00:00]ARC v1 Solution [00:07:20]Evolutionary Python Approach [00:08:00]Trade-offs in Depth vs. Breadth [00:10:33]ARC v2 Improvements [00:11:45]Natural Language Shift [00:12:35]Model Thinking Enhancements [00:13:05]Neural Networks vs. Symbolism Debate [00:14:24]Turing Completeness Discussion [00:15:24]Continual Learning Challenges [00:19:12]Reasoning and Intelligence [00:29:33]Knowledge Trees and Synthesis [00:50:15]Creativity and Invention [00:56:41]Future Directions and Closing [01:02:30]REFS:Jeremy’s 2024 article on winning ARCAGI1-pubhttps://jeremyberman.substack.com/p/how-i-got-a-record-536-on-arc-agiGetting 50% (SoTA) on ARC-AGI with GPT-4o [Greenblatt]https://blog.redwoodresearch.org/p/getting-50-sota-on-arc-agi-with-gpt https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z9j3wB1RRGA [his MLST interview]A Thousand Brains: A New Theory of Intelligence [Hawkins]https://www.amazon.com/Thousand-Brains-New-Theory-Intelligence/dp/1541675819https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6VQILbDqaI4 [MLST interview]Francois Chollet + Mike Knoop’s labhttps://ndea.com/On the Measure of Intelligence [Chollet]https://arxiv.org/abs/1911.01547On the Biology of a Large Language Model [Anthropic]https://transformer-circuits.pub/2025/attribution-graphs/biology.html The ARChitects [won 2024 ARC-AGI-1-private]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mTX_sAq--zY Connectionism critique 1998 [Fodor/Pylshyn]https://uh.edu/~garson/F&P1.PDF Questioning Representational Optimism in Deep Learning: The Fractured Entangled Representation Hypothesis [Kumar/Stanley]https://arxiv.org/pdf/2505.11581 AlphaEvolve interview (also program synthesis)https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vC9nAosXrJw ShinkaEvolve: Evolving New Algorithms with LLMs, Orders of Magnitude More Efficiently [Lange et al]https://sakana.ai/shinka-evolve/ Deep learning with Python Rev 3 [Chollet] - READ CHAPTER 19 NOW!https://deeplearningwithpython.io/</p>

Full Transcript